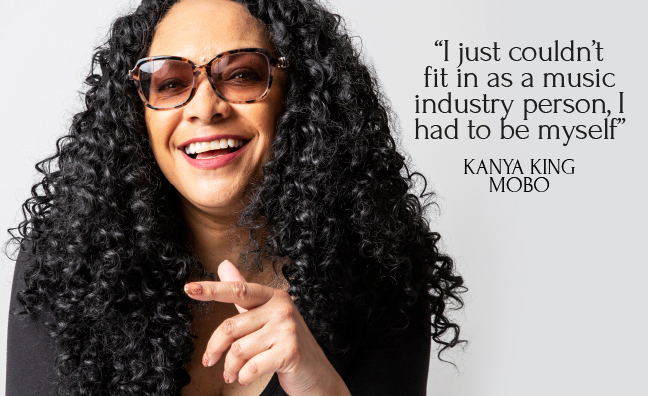

Kanya King is a legend, in the music industry and beyond. Since founding the MOBO Awards in the mid-’90s, she has elevated Black music to unprecedented heights, inspiring wave after wave of artists and executives to break boundaries in the UK and around the world. Here, the winner of The Strat at the Music Week Awards 2021 looks back at an illustrious career and, as the MOBOs turns 25, plots what’s next...

WORDS: Colleen Harris PHOTOS: Louise Haywood-Schiefer

It’s a lonely road to success. And the path less travelled can be isolating for an industry innovator challenging the status quo. Kanya King CBE knows it well, having dedicated more than two decades to championing Black music in the UK. Before the 2021 Music Week Awards Strat winner founded the first Music Of Black Origin (MOBO) Awards in 1996, few Black British artists were given their flowers in the way today’s homegrown talent are. The desire to change things is testament to King’s upbringing, a mixed-race child born in Kilburn, North London and raised by a Ghanaian father and Irish mother, who was ostracised from her family. Witnessing discrimination levelled at both her parents fuelled King’s mission to fight for better representation in a creative sector that impacted her self-image.

“I witnessed so many inequalities growing up,” she tells Music Week, settling into a long interview to celebrate The Strat, not to mention the 25th anniversary of the MOBOs. “My father had a strong African accent, he struggled to get a job. There was no kind of pride, you’d watch things at Christmas time, like Zulu, and the images of Africans were of savages – the very opposite [of reality]. My father was very elegant.”

King has defied the doubters to become one of Britain’s most influential executives. After beginning her career in TV, 25 years ago she launched the UK’s most prominent Black awards ceremony, which has laid the foundations for a golden generation of UK Black music and been televised in over 55 countries. Stepping into a space to demand change is not easy, but it’s a challenge she was prepared for.

“Resilience is a muscle that you build, and I had many obstacles growing up,” says King. “What I would say is the resilience built from my childhood certainly allowed me to be flexible and adaptable. I had many trials and tribulations, so you build a tenacity to deal with things. Rejection, to me, became normalised.”

King found herself facing rejection when launching MOBO. Unlike the climate of today, conversations about race and inequality were shunned, as she recalls.

“I remember being told, ‘You’ve got a chip on your shoulder, why are you talking about race all the time?’” says King. “You don’t want to be told that, you don’t want to be thought of as that person.”

In that respect, much has changed. Confronting racism is a far less lonely road since the murder of George Floyd last year and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement. In June 2020, King’s powerful open letter to the culture secretary Oliver Dowden called for racism in the music industry to “no longer be swept under a red carpet”.

It fell on the ears of a music industry ready to listen, learn and support the Blackout Tuesday initiative and the formation of the Black Music Coalition.

To build on the momentum, King is focusing on projects such as her latest initiative MOBOLISE, a platform that aims to connect Black creative and tech talent to mentors, networks and career opportunities. It’s a taste of what’s to come for the brand, expanding on its existing work with MOBO Help Musicians Fund and MOBO Unsung.

“One of the reasons why we had MOBO Help Musicians Fund and MOBO Unsung is because you realise that people are not the finished product; they need the resources to create, as well as mentors who look like them,” says King. “That has been very successful in terms of the application and the money that has gone out, because it’s giving business support as well. Money is one thing, but I think business support and mentoring makes all the difference.”

By providing a network of industry connections for Black creatives, businesses and talent through MOBOLISE, King hopes to bridge the gap that hindered her own journey.

“What would have made the biggest difference is to have had allies, to be quite honest with you,” declares King. “Whether it’s mentorship or sponsorship, having someone who could champion you is key. What it means is they are just proactively doing it, they talk about you and the work you’re doing when you’re not in the room.”

Whether in the room, or out of it, King’s name sits rightfully alongside pioneers in an industry that is still considered stubbornly white and male. Black, Asian and minority ethnic people make up 19.9% of executive roles and women 40.4%, according to the latest UK Music Diversity Report.

“I remember in the beginning I was told that I should have my hair in a bun to be taken seriously, and not wear make-up otherwise I would look like an artist,” she says. “[This was] to fit in as an industry person, but I just couldn’t do it. I just needed to be myself. It’s amazing now, because you realise things have changed so much. Women used to wear the big power suits and were encouraged not to look feminine. But I just felt I had to be who I am, that’s it. In doing so, you find your tribe; some people will like it and some people won’t.”

The power of authenticity has been a bedrock of King’s career trajectory, from start-up entrepreneur to renowned trailblazer. Never compromising on what it means to be a woman in business, she is an advocate for other female leaders such as Carla Marie Williams who founded Girls I Rate, a movement championing young female creatives, who make up just 20% of British songwriters.

King has become synonymous with turning obstacles into opportunities, leading her own fight to break down barriers. And this month she breaks down another, becoming the first woman of colour to win Music Week’s Strat award in recognition of a truly pioneering talent. Celebrating that honour, she reflects on the peaks and pitfalls of her illustrious career, the state of the Black British music scene, and the future of the MOBO brand...

What does it mean to be the first woman of colour to win The Strat?

“I’m speechless to be honest with you. I feel like I’m here on behalf of all those who have gone before me, who should have been recognised and celebrated – but are not. That’s how I feel. These moments in life are bigger than ourselves. There have been extraordinary females who have done wonderful things. One of the things I’ve been campaigning for and championing my whole life is better representation. So this is like, in a way, a milestone because I’m hoping there’ll be many more to follow, and things will change.”

When Darcus Beese won The Strat in 2019, he said that being the first person of colour to win it “had to be a proud moment” and that the entire industry looks completely different to the one he walked into. Does that resonate?

“Totally. Over the years I’ve been at many meetings and board meetings, and been the only person of colour. I felt very much an outsider; it felt at times like a hostile environment. I haven’t come from a traditional path like others in the music industry. There haven’t been many Black execs, there were few when I started so, yes, I recognise exactly what [he’s] saying.”

It sounds like you weren’t knocking on doors, but banging them down...

“People didn’t want to take my calls. I remember meeting someone, I can’t remember when it was, a senior person in the industry who said it was amazing we’re still around because there were discussions at a high level about how to get rid of MOBO.”

Were you surprised to hear that?

“It’s one of those things where you feel it, but you have no evidence. Does that make sense? You know that you’re not getting the support, [or] when someone was a MOBO Award winner [it would] be taken off press releases, and only mentioned [when] something was negative.”

You said you didn’t come through the traditional path, so what did you do to get MOBO off the ground?

“I reached out to people in the music industry like Dej Mahoney and Keith Harris. Keith introduced me to Dej, these were very senior record company executives. I had a conversation with them about what I wanted to do, and I lacked a lot of experience at the time because I didn’t come from the music industry. But for what I lacked in experience, I had a lot of drive, passion and determination. I took a lot of risk in starting the MOBO Awards, in terms of re-mortgaging my house to pay for production. There were no guarantees that it would be a success, but I just had to give it everything. A lot of people were polite, if you know what I mean, but I’ve struggled to get the support.”

How did you deal with that?

“Over the years, it’s been a very lonely battle talking about inequality when it wasn’t the thing to do at the time. There was no social media, so if you talked about inequality you risked being ostracised or marginalised, or it affected your career. I just had to give it everything. My plan B was also my plan A, and I was determined not to lose all the money I was investing and, ultimately, my home. I was taking all sorts of risks but I was keeping them quiet because I didn’t know who to turn to. I knew my mum had concerns, because I come from a large family of nine children, and we had a lot of ill health in our family. But I knew even if things were not a success, I’ve always felt that success is not final, failure is not the end. It’s just finding the courage to continue that counts.”

What was your vision for MOBO? Have you gone beyond it and, if so, by how far?

“I don’t think there has been a turning point, there have been lots of tiny actions that all led up to the point where we are now. There’s a momentum you build, and the success you achieve when you’re just putting in the effort consistently and I think that’s indicative of many other companies. MOBO was founded because there wasn’t that kind of mainstream platform for Black music or culture, there was a huge void in the music industry’s representation. In the beginning, I was talking to many organisations, trying to get things to change and realising it just wasn’t an easy task. I just felt that if I believed in this so much, I needed to put my money where my mouth was. I grew up being surrounded by many creative people who were immensely talented but one by one I was seeing them go by the wayside, their talents going to waste because they couldn’t access opportunities in a sector which is very much about who you know. It’s always been hugely important for me that people should be able to hear and see themselves reflected on our screens and be celebrated for their work. I think music and arts are so important to our lives and have an impact on how we see ourselves. I’ve witnessed so many people who’ve had mental health issues because they could not be who they are, they could not feel proud of being Black, or being part of the LGBTQ community, or just feeling less than [others]. I’ve always felt that kind of injustice, and I wanted people to be able to be proud of who they are.”

What are the best examples of artists that have been boosted by the MOBOs?

“In a way, it’s best to hear from the talent itself. I know Krept & Konan have talked about the impact on their career, they talked about performing at the MOBO Awards and the huge difference it made. We’ve been supporting African music since day one, from having Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Youssou N’Dour, to [modern] Afrobeats. I remember an African artist saying to me after they won a MOBO that the commercial and sponsorship deals they got had been incredible. A lot of the African artists have told us that. There have been many artists who’ve gone on record about the massive impact it’s made to their lives, whether getting them airplay, sales, endorsements and commercial deals, or motivating them to realise, ‘Well actually, I’m good at this.’ It validates all their hard work.”

It must be nice to hear that. Do you take that as validation yourself, and think, ‘Wow, look at the impact we’ve had’?

“I saw an old link the other day of Akala being interviewed on a red carpet, he was talking about what MOBO has done for the UK Black music scene, especially for independent artists, and how it’s made all the difference to his and others’ careers. So yes, it makes you feel incredibly proud. It makes you want to do more. Ultimately, we all have different drivers in life. And my background led me to realise, ‘Well, you’re on this earth for a short time so why not make it count, the time that you have?’ And that has always been important to me.”

Previously, Black UK acts looked to the US for success, but there has been a shift and a growing confidence in homegrown Black talent. Has MOBO played a part in that?

“Most definitely. We’ve been celebrating such a diverse range of genres whether it’s reggae, gospel, Afrobeats, grime, all of that. The other day someone posted on Instagram, ‘Oh my God, this was a legendary event at the MOBO awards.’ They had a clip of Jay-Z when he picked up an award at the Royal Albert Hall, Destiny’s Child performed and they also picked up awards and there was Damon Dash and the whole Jay-Z collective. It is amazing to think that there have been phenomenal artists, such as Sade coming out of retirement to perform at the MOBO Awards because she felt that was important. That was a huge amount of pride. There’s been a diverse range of artists that have performed on the MOBO stage and I think that has inspired a lot of young talent, it’s motivated them to want to do more, dare more and be more. MOBO Unsung is supporting artists sometimes very early on, when they have no representation or anything, like Tiana Major9 – to see her on her journey and be nominated for Grammys and performing at the MOBO Awards is incredibly rewarding. Through MOBO Unsung or MOBO Help Musicians Fund, witnessing artists who are given the support they need to make their mark on the world without compromising their art is really important, because you want people’s talents to shine, you want them to achieve their dreams.”

Why is UK rap growing so exponentially?

“I just think talent is working more together, which is absolutely brilliant. I think that makes such a massive difference. It’s artists supporting other artists, they tap into each other’s fanbases. There’s obviously social media, and the internet has cut out a lot of people in the middle as well. There’s so much creativity and technology, which is brilliant to see. There’s also a sense of pride and identity; music and that social message have always gone hand in hand, especially for Black music and culture, with talent being very vocal about that. It’s an incredibly creative, exciting time. I think artists are creating more politically-charged music with less fear of a backlash, or they’re creating sounds and visuals that reflect the times that we’re in. Position can make a huge difference; we’ve seen that with the [scholarship programme] Stormzy is doing at the University Of Cambridge.”

What has MOBO done for people behind the scenes?

“MOBO always had a socially conscious responsibility. We partnered with the NHS on many occasions. NHS Blood and Transplant had a very clear problem, not enough of the Black community would donate blood and this was leading to issues with research into disease and cure. There were a number of main objectives they wanted to achieve; one of them was to raise awareness of the need for more donors, they wanted to target a young, less engaged audience. What we wanted to do is change the narrative about Black music, to say that Black music could be a positive force for good. So one thing is using our voice for social campaigns, but there’s an ecosystem of opportunities. Sometimes I get emails out of the blue from executives who say, ‘Thank you for giving me my first opportunity.’”

Are you aware of how the wider industry perceives MOBO?

“I remember when we were trying to get sponsorship, someone in marketing at a company said to me, ‘Oh, we give a lot more money to events that deliver half of what you do.’ It wasn’t surprising, that is what happened. The truth is, at the senior levels, you look at the creative industry sector, pre-Covid, it was the fastest growing sector in the UK economy, one in 11 jobs was created in the creative industry sector, yet Black representation was very low. Prior to George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, inequalities and injustices weren’t being talked about. People would give opportunities to people who sounded and looked like them. But that affects everything; that affects sponsorship, it affects suppliers. We have a partnership with London Theatre Consortium. We realise there aren’t enough leaders who are running cultural institutions, so we’ve worked with them and seen these leaders going on to do incredible things and demystifying what it is to work on a board. Those things are just so important for us, there have been so many internships, apprenticeships, creating role models, all of that, we can see the difference it makes, and that’s really important.”

How do you think you’ve grown as a leader?

“When starting out I wasn’t surrounded by advisors, I didn’t have a mentor or any of those things. I’ve learned to listen, being a good listener is important. I’ve learned to evaluate a situation from others’ perspectives, and to put yourself in someone else’s shoes. Being a leader isn’t about knowing everything. Each team member brings their own expertise and together they are powerful. I’ve learned to be curious, to ask for help when I need it. Asking for help doesn’t make you any less of an expert. You can’t do it all on your own and so you might as well own that, show maturity and be willing to learn. There are a lot of things that I’ve certainly developed, and I’ve certainly grown as a leader.”

Do you see yourself as a natural entrepreneur?

“You know, the irony is that most of the jobs I’ve had, I’ve created myself. When I worked in television, I was a researcher at The Chrystal Rose Show. It was one of those where you had to make things happen, get on the phone and book people for shows. I guess what I learned there is whatever I do, I try and do 100%. Regardless of whether I was working for myself or anybody else, I always put 100% into it. My father used to say, ‘Be the best you can be.’ When I look back at what I’ve done, that wasn’t necessarily the intention. I just felt that there was a gap. I wanted to see more Black role models, there weren’t any really and I jumped at the chance to support them.”

Lastly, what do you want to achieve next?

“I don’t necessarily have a five or 10-year plan, but MOBOLISE, and telling the MOBO story, are important. I want there to be an opportunity to archive what we’ve collected and tell the story so it can hopefully go on and impact others. MOBOLISE is a big priority, for me it’s about how we can work with others for a bigger purpose and a wider impact. We’re going to be working with things like Google Digital Garage to provide skills development, we’ve got webinars that we’re looking to do on skills development for talent. We were also just keen to make sure that there’s not just training. That’s why we created MOBOLISE because sure, we can get into training and skills development, but we have got to make sure that there are jobs as well, and that’s a key focus for us. So yes, we shall see what’s next...”