When it comes to artist development, few acts can tell a story quite like Sampha. Since his internship at his record label, the elusive talent’s achievements include winning the Mercury Prize and working with a litany of stars including Drake, Solange and Kendrick Lamar. To mark the arrival of his second record Lahai, Music Week takes a trip into his world, alongside team Young, to talk life and death, collaboration and becoming a star…

WORDS: BEN HOMEWOOD COVER PHOTO: TRINITY ELLIS PHOTOS: JESSE CRANKSON

Sampha eyes the drink on the table in front of him longingly. In an empty café on a sodden September afternoon, he’s in the middle of the first of many long, wandering answers, and it’s as if even the slightest movement towards his cup might derail his train of thought. Surely no one in this particular North London coffee shop has ever gazed at a matcha latte with such intensity. But Sampha, in a brown corduroy jacket, is no ordinary customer, and there’s an intensity to the way he does just about everything.

“I am someone who is going through life and expressing some of those emotions in music,” offers the singer, songwriter and producer, as we begin discussing Lahai, his second album (due October 20 via Young) and the follow-up to 2017’s Mercury Prize winner, Process. “A sequence of chords might make you tear up. It’s a bit difficult to say, ‘Well, it did that because of…’ I haven’t really got into the neurology of music, but there is something there. Music operates on a level where you don’t need to understand what the lyrics are saying to feel the emotion.”

Sampha’s music is renowned for its emotional heft, while his transportive falsetto, universal lyricism and earthy production style have prompted a growing and glowing list of collaborators to seek him out. Quietly, he has spent the decade since he burst into public consciousness – thanks to a feature on Drake’s Too Much (281,455 sales, according to the Official Charts Company) – becoming one of the most revered creative talents of his generation. Before his debut was even released, he had also worked with Beyoncé, Solange, Frank Ocean, Kanye West, FKA Twigs, Sbtrkt, Jessie Ware and more. In the wake of its release, he has added David Byrne, Kendrick Lamar, Stormzy and Travis Scott to that list.

“I sit in the eye of the Sampha storm, so I think it’s the biggest thing in the world!” says Young founder Caius Pawson, who has known Sampha since he interned at the indie label formerly known as Young Turks in its nascent days in XL’s West London office. “I was struck by his raw qualities and his rare humility. Now, I hear artists talk about him, I see him on other people’s records, I can see the influence he’s had, even beyond music. It’s his ability to normalise grief, his empathy, as well as his musicality, that have gone far. His way of staying true to himself is a massive influence. The new record sounds like Sampha, and that in itself is a success, that’s pure artistry. As long as he’s doing that, we can’t ask for any more.”

But Sampha has proved a somewhat reluctant superstar. He initially wanted to be a beatmaker when he arrived at Young, and had a mentor in experimental producer Kwes, who he’d met on Myspace. But the seeds of what was to come were sown when he played demos of what would become his 2010 EP Sundanza in the office.

“He’d put down a scratch vocal and obviously it was heaven sent,” recalls Pawson. “Remember, he was an intern at the time. He had a habit of not answering questions in meetings, but if you asked him about a song he would sing it on the spot. It was all part of him realising himself and his artistry, finding confidence. He wasn’t an intern for very long, his excellence lit up the room.”

Pawson, who was brought into Beggars Group by XL boss Richard Russell, notes that Sampha wasn’t the only great talent in the building.

“This was a period where Adele, after 19, came back into Beggars,” he says. “She worked at Rough Trade Shops and was in XL so much she might as well have been an intern, so it felt quite natural.”

Indeed, Adele once asked for a day off without saying why, and the reason turned out to be a gig with Etta James at the Hollywood Bowl. And while Sampha is yet to match Adele’s commercial impact, his team see a similarly impactful talent.

Hannah Partington, his day-to-day manager for the past six years, describes him as “an incredibly humble, empathetic and considerate human being, almost to a fault”.

“While he has a multitude of concepts and ideas coursing through his mind, he also has a strong intuition that navigates him through to the emotional core of what he’s creating,” she adds. “And, of course, incredible technical chops.”

Much of the feeling that defines Sampha’s work centres around family. Sampha Lahai Sisay, to use his full name, titled the new record using his middle name (also his paternal grandfather’s name) while two of his four elder brothers, Sanie and Ernest, helped fire his interest in music growing up in Morden, South London. His family moved to the UK from Sierra Leone before Sampha was born and his father Joe would fill the house with the sound of CDs ranging from Pavarotti to Malian singer Oumou Sangaré. He passed away after battling cancer in 1998 and in 2015 Sampha’s mother Binty died after fighting the same disease.

Process was heavy with grief and its stand-out track (No One Knows Me) Like The Piano laid bare his ability to use music to channel universal feelings. Process hit No.7 in the UK and has 73,227 sales, while No One… is his biggest single with 252,806.

The lead-up to Lahai brought new beginnings, as Sampha and his long-term partner became parents in 2020. Skipping between jazz, hip-hop, soul, jungle, electronica and West African sounds, its 14 tracks deal with human connection, spirituality and the passing of time. Having dealt so explicitly with death on Process, he’s now able to write about new life too, removing the veil of mystery around him at the same time. On Only, he promises to, ‘Take a mic and press record and speak the truth only’.

“I’m grappling with trying to embrace how perspective changes with loss and how grief isn’t finite,” Sampha says, his quiet speaking voice competing against the sound of washing up in the background. “It just changes shape, it resurfaces when joy might appear and there’s a dance between the two. It’s interesting to see the magic in having a child as well. You have to be patient and re-evaluate your presumptions about life and that makes you question things like social conventions, obedience and how you were brought up. Also, it’s about recognising how having a kid is not going to fix you, that there are certain challenges only you can face.”

With influences including Kodwo Eshun’s study of the music of Afrofuturism, More Brilliant Than The Sun: Adventures In Sonic Fiction, and Richard Bach’s fable Jonathan Livingston Seagull (which Sampha’s brother used to read him as a child), Lahai operates on a more cosmic level, too. Our chat also meanders into far out territory.

“There’s something to be said for the journey and the magic in everything,” Sampha muses. “I feel like I sometimes have a glimpse or a feeling of being able to observe the magical well that things emanate from and I feel like I’m not in control of it.”

He uses our very interview to make his point, as our exchange enters a mystical realm far beyond the drizzle and traffic outside.

“It’s like the words I’m speaking to you now, how I string them together and I don’t stumble,” he says. “You put things together, you find things and you arrange them, but everything’s already here, everything is connected in some way and we just put it together.”

This is how Sampha operates, flitting between dreamlike vagueness and precision. So, having interrogated himself to such a degree on Lahai, is he happy with the outcome?

“Um… Yeahhh,” he says, smiling at his hesitation. “I am definitely happy, but it’s strange. There are times where, because of the subject matter, it feels like it’s still evolving in my head.”

The weirdness of an album he completed months ago feeling unfinished is not lost on Sampha. After making his live return at St John’s Church in Hackney in June, he re-recorded Satellite Business, the skittering, minute-long fifth track that contains the line, ‘Through the eyes of my child/I can see you in my vision’.

“I wrote that song right at the end of the record and it felt like it held the conceptual crux of what I was trying to get at,” he says. “It just took on a life of its own, it’s about the concept of time and things not being as linear [as we think], and that just fed into the idea of drawing from the past to look at the future.”

After what has felt like an age, Sampha allows himself a drink, and silence settles for a few seconds. It’s almost too obvious to point this out, but it seems there’s a lot going on inside his head.

“Hmm,” he nods in agreement, before explaining that bar co-producer El Guincho (who used to release records on Young Turks), he didn’t discuss Lahai’s subject matter with his collaborators, a long list that includes Yaeji, Léa Sen, Laura Groves, Kwake Bass, Yussef Dayes, Ibeyi and more.

Did internalising all that make things more complicated?

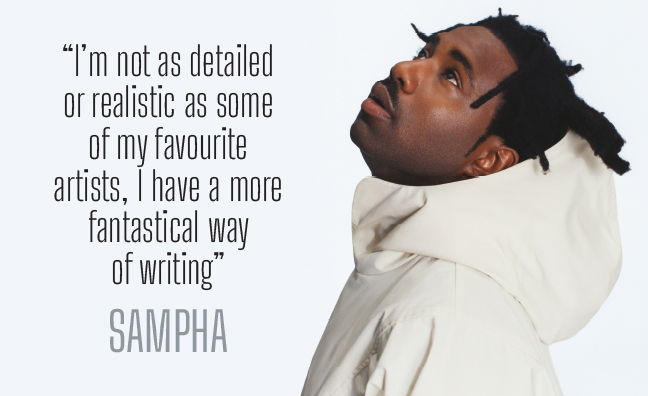

“No, it was quite a fragmented, impressionistic process,” he says, explaining that there’s no pattern to his lyric writing. “I’m not as detailed or realistic as some of my favourite artists in rap or hip-hop, or even Johnny Cash or someone who can write about the nuances of a particular relationship. I might have a more fantastical or veiled way of writing. Most of the lyrics come from a moment in my life that only makes sense to me. But I do write for myself, I need to, it’s therapy. I’m someone with things [going on] and music is an outlet…”

As Sampha tells his story, one softly-spoken monologue at a time, the fact that he’s come so far as a recording artist feels progressively more remarkable.

With its creation impacted by the final years of his mother’s life, Process saw the light of day almost a decade after he first arrived at Young, and Lahai is coming out nearly seven years later. Even with the pandemic and parenthood in the mix, it feels like a long time away by today’s content-hungry standards.

“It is pretty long!” he says, laughing. “It took me a couple of years to get into the groove of figuring out what I wanted to do. Also writing lyrics and all that stuff, it’s not what I do. I’ve been in the studio with people who write [quickly] and it’s different… It’s the same with producers who can come up with stuff really quickly. Not to say I can’t [do that] and I don’t want to make the creative process [sound] overly mythical, but I do tend to take my time.”

Sampha’s team has consistently allowed him that space, and now they can look back on a compelling artist development story, a landmark independent success.

“There was a beautiful moment when Sampha was working with Drake,” says Caius Pawson. “He came back and said, ‘I was sat on the sofa and Drake told me about his life, and then he got in the booth and said the exact same thing and there was a connection to truth there that I’m not ready for.’ Then he came back from a Kanye writing camp years later and said, ‘Right, it’s about time I start making my own work now.’ That culminated in Process and the years since have just seen him ripen. He’s full of confidence.”

Young has found similar slow burn success with The xx (and subsequent solo projects from all three members) and FKA Twigs.

“Nothing is ever rushed, you’d only ever rush something if you felt the added pressure would help the artistic process,” says Pawson. “Artistic development is the number one thing we’re interested in: where someone is going. I’ve always felt that the artists people respond to are the ones who are totally unique, and you can only be that if you’re given space and are free from interference.”

Young is the only place Pawson has ever worked, so he can’t compare it to how the wider industry operates, but he credits Beggars Group chairman Martin Mills and XL’s Richard Russell with a crucial role in the company’s success.

“They’ve given me the space to work like this which has allowed me to give the artists space to work like they do,” he says.

Sampha has come to define Young’s story. As well as collaborating with “basically everyone” on the label, he was the first act to move into one of the five studios in the company’s new East London HQ.

“As much as we’ve been there every step of his journey, he’s been here for every step of ours,” Pawson says.

Partington says Young, which moved its publishing operation to Sony Music Publishing in 2018, has developed a strong operation around Sampha.

“His internal creative convictions are resolute, but I wanted him to feel comfortable articulating that outwards,” she says. “And of course, [we offer] a dose of healthy resistance to help evolve ideas. What we do is figure out which idea is the one to act upon, to create the space for Sampha to follow his instincts, with the people he wants to help realise them.”

Pawson, Partington and Sampha himself all emphasise his increased openness to inviting collaborators in on Lahai, but the tracklist is notable for an absence of credited features. Were they not tempted to go after a big name or two?

“There are lots of people who I’ve built that relationship up with where [something] might happen later down the line, and there are maybe one or two people that I hollered at that couldn’t make the sessions who would be seen as bigger,” Sampha offers, without naming names. “But I’ve never really forced [anything], I’m learning how to reach out to people and find the right time. It’s never for reasons of using them for currency in terms of appealing to a wider fanbase or selling the record, it’s usually because I’m a deep fan of their work and artistically they seem right. If I do things for [those] other reasons, I’ll regret it.”

“I think Sampha finds it easier to say yes to other artists’ requests and much harder to actually reach out himself,” smiles Pawson. “There were moments when we looked to open it up to people, but it never seemed to work. In the streaming age, it’s almost the same being on other people’s records as it is having them on your own in terms of opening up to new audiences. Whilst features are wonderful and definitely part of his plan, seeing him come back having learnt something different from everyone is the most enriching bit of it all.”

Drake was Sampha’s first major collaborator, and working with the Canadian on 2013’s Nothing Was The Same had a profound impact.

“It was cool, but in some ways it was intense for me,” he says. “Psychologically, I can find it hard to balance the complexities of having a presence online or having people notice you, so that threw me off a little bit and I became slightly stand-offish from social media. That’s been my disposition, but I’m coming back to it now.”

The increased exposure inevitably meant that offers began to stack up, many of which were from Sampha’s favourite artists. Gradually, he says, he learned to open up.

“I’ve gone through a journey with it and I’m at a different place now in terms of thinking about how I work with people, who I’m working with and what I’m doing,” he says.

Pawson namechecks Kendrick Lamar, Solange and Stormzy as three pivotal relationships, and notes that Sampha “couldn’t have had more fun” than he did during a four-day jam session in the South of France writing for Travis Scott’s recent No.1 album Utopia.

“With Kendrick and Solange, Sampha would come back and say, ‘I can see how well this can be done,’” says Pawson.

Sampha’s own reflections on collaborating are fascinating.

“Kendrick is a real noble… He’s a bit of a guru of a person, he’s really responsive and really hands-on with people, with me,” he says, recalling his contribution to last year’s seismic Mr Morale & The Big Steppers. “He gave me confidence in the jams. He came over to London and I jammed with him for a couple of days, Father Time came out of those and there were more tracks we were working on. Then we were just back and forth on text, when he had something he’d be like, ‘Could you write to this?’”

We ask how deep their relationship goes.

“I mean, we have a back and forth, it’s friendly, we’re not like best buddies but I’ll text him and he’ll text back,” he smiles. “He’s such an important artist and he works on many different levels. Even his performance, his movement, watching him express himself visually, taking ownership of his creativity, all those things are part of the holistic aspect that I’ve taken in. It was inspiring just to take it on, I’m like a sponge. Solange is similar, the level she did everything at, visuals, dance, singing, music making, I put them in a similar space in that context.”

If Sampha stops short of explicitly saying he’s aiming at such levels, it’s understandable. His presence is growing (he has almost 3.5 million monthly listeners on Spotify, where Lahai’s first single Spirit 2.0 has passed 3.3m streams), but he’s not about to start chasing hits.

“When I did begin to write songs, it was more for the sake of writing than imagining myself doing well out there as an artist, which is probably why I’ve never done so well in respect to writing a lot of music or feeling like I know exactly what I do,” he says. “When I was younger, watching Michael Jackson and stuff I used to think, ‘I could be on stage,’ but when I got older, I imagined being on the production side. Even when I worked with Sbtrkt at 18, 19, he had more of an idea I could sing than I did.”

Eventually, the choice was taken out of his hands.

“People just kind of gravitated towards my voice,” he says. “And I enjoyed singing and playing the piano, even though early on I was like, ‘I’m never gonna do that, it’s not for me.’ But look at me now!”

His shoulders jiggle as he laughs at that last sentence, and it seems absurd that he didn’t realise his gifts sooner.

“I would sing in the shower and at home with the piano, but I never wrote songs unless I needed to,” he says. “It has always come from a place of intuition, not something preconceived. I’m a pretty scatterbrained person, I’m better at getting into a situation, then once I’m in it I can focus. I’m into the tradition of freestyling rather than writing things down.”

Perhaps his particular evolution is the key to Sampha’s appeal: his songs sound so complete because of his technical skill, so honest because of his unfiltered approach and so natural because of his will to simply let them take shape, rather than force anything.

His place in the musical ecosystem is assured, but Sampha will remain within the experimental London scene that continues to nurture him. Don’t expect a move into hitmaking any time soon.

“I’ve done a few of those songwriting camps and it’s not my favourite place to be,” he says. “Sometimes because the artist isn’t there it can be difficult, I like to have feedback.”

Community is important to Sampha and one thing he is prepared to acknowledge is that his experience could be beneficial to others coming up behind him.

“I have certain friends who will give game and be honest with each other,” he says. “It’s nice to [share] artistic interests, but your interests as a person are the main thing. Some perspectives people might have could be those of the company they work for, so it is important to have people I can talk to. And when I come across younger, less experienced artists, I try to be as honest as I can about my experience and say the things I would or wouldn’t do and [tell them] to recognise their value more than anything. To try and be as diligent as they can.”

It’s not hard to imagine Sampha’s own willpower has been tested since he blew up, but if the industry sharks have ever circled to threaten his bond with Young, he doesn’t let on.

“Obviously, the music industry is evolving and naturally the older you get, the more clued up you become and the more your relationships evolve,” he says. “I have a different standpoint to where I once was as an artist, and you recognise how the historical system is not always set up in favour of artists. There are always things to be improved upon and you have to be open to a certain level of fluidity. I have a good relationship with Young, hopefully I’ll make more records with them, because I appreciate their creative input.”

Pawson says the idea of major labels poaching independent artists is outdated.

“I think Young, XL and Beggars are at the point where we’re past that,” he reasons. “Beggars has an international set-up that rivals the majors. Adele’s first three albums, nearly 100 million records sold, somewhat proves that you don’t have to have distribution and shareholders to have massive success. The sorts of relationships that Young tries to develop are long-term and based on total artistic freedom and massive ambition to make the best possible work. I strongly believe that if you challenge yourself and make something that’s totally unique to you, the rest of the industry and financial success will follow.”

With that in mind, what would constitute success for Lahai in Pawson’s eyes?

“First and foremost, I want Sampha to be widely recognised as the artist that he is, by his peers, the media and fans,” he says. “Sales target-wise, we tend to play a slightly longer game. Process ended up selling half a million copies worldwide. I would expect this to do very well, but with multiple re-releases by pop stars, chart position is almost impossible to predict. But Sampha has got a very, very strong US following, and like most Beggars acts, he does very well across most international territories. We aim for an 18-month campaign with a bunch of activations to lodge Sampha into the culture, we want him to have a very long life. If this album is a success, that will be Sampha’s success.”

Pawson’s stance feels refreshing. The fact that, as he talks, loud moo-ing can be heard in the background underlines the idea that this isn’t a typical exec interview. Pawson is talking to Music Week from a cycling holiday in Austria and, he says, “The farmer where we are has let the cows out and they’re bigger than horses!”

So does he really not want to bat any numbers around when it comes to targets for Lahai?

“Look,” he says, “I want a trillion streams, I just don’t want a single one if it gets in the way of a record being as good as it can be.”

As for Sampha, progress mostly comes down to being able to make more music and expand his reach. Added to that, he sees the value in being more candid, Lahai is deeper, richer, more adventurous than Process and it goes some way to unlocking his enigma.

His jacket is buttoned up and we’re about to head back outside into the London rain, but there’s time for one last patient observation.

“What do I do if it gets critically panned?” he asks jokingly. “How much of my ego is really [wrapped up in it]? Am I going to say, ‘Wait, what do you mean? This is excellent! How dare you speak against this record and have an opinion on it?’ I feel like there’s a part of me that’s like a rottweiler, just ready for someone to say something, but also there’s a bit of me where I haven’t really thought about it.”

As ever, Sampha is more concerned with the work itself.

“It’s a weird industry to be in, the dopamine and serotonin hits you get from the adoration and stuff can mess up your ability to feel, basically,” he concludes. “It’s a fine balance, but connecting to reality and life, rather than the other bits, that’s the real success.”