The last time The 1975 released an album, the controversial chart-topping band nearly imploded for good. Returning revitalised two years on with Being Funny In A Foreign Language, they have rediscovered their identity and made a pop-heavy guitar album that is set to confound expectations all over again. To hear its story and look ahead to what promises to be another rollercoaster campaign, Music Week meets band leader Matthew Healy, plus his manager and Dirty Hit label boss Jamie Oborne and ICM Partners’ Matt Bates. Strap in for a tale of reinvention, drama and music industry mayhem…

WORDS: BEN HOMEWOOD

COVER PHOTO: JORDAN CURTIS HUGHES

PHOTOS: SAMUEL BRADLEY

Matthew Healy has a reminder for anyone who has forgotten who his band, The 1975, are over the past two years.

“It’s The Inbetweeners” he says, laughing. “It’s not this austere, cool, sleek thing, it’s a bunch of fucking gimps.”

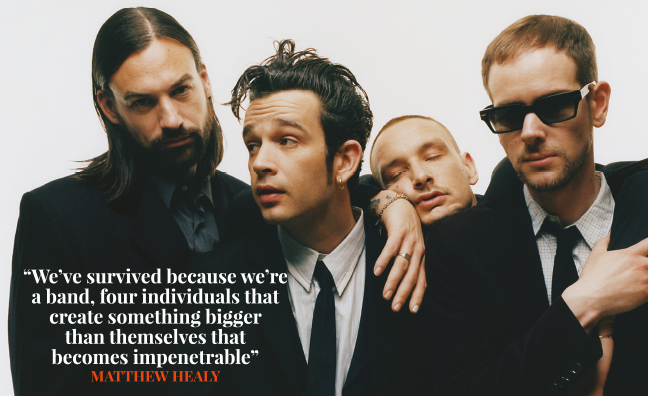

The Inbetweeners aren’t the only adolescent comedy characters he mentions in his first Music Week interview since April 2020, when we spoke during the chaotic onset of the coronavirus pandemic. He also brings up Harry Enfield’s Kevin The Teenager sketch as part of an explanation of his unfiltered approach to talking to the press, which has led to an expectation that he’ll always say something incendiary. As The 1975 – completed by guitarist Adam Hann, bassist Ross MacDonald and drummer and producer George Daniel – prepare to release their fifth album, Being Funny In A Foreign Language via Dirty Hit on October 14, Healy wants to explain himself.

“‘I don’t care’ is a cliché and it rubs off as a bit Kevin & Perry, but I don’t know how to emotionally be different, so censoring myself would be so blunt,” he says. “If I went into an interview and said, ‘Right, I’m not gonna give him anything,’ it would be like… I might as well go and audition for a film, it would be so abstract.”

Some artists are more considered, able to concentrate on marketing what it is they are promoting, but not Healy.

“I don’t care about that, I don’t have time,” he offers.

The 1975’s frontman is a wild conversationalist and a compulsive tangent pursuer. But, after some time away, he’s added deliberation and qualification to his approach.

The soundbite headlines, he says, began to grate. And when you do as many interviews as Healy was while promoting The 1975’s back-to-back pair of pre-Covid No.1 albums A Brief Inquiry Into Online Relationships (253,736 sales, OCC) and Notes On A Conditional Form (84,483), it’s easy to see why.

“It was like, ‘I’m just gonna have a conversation and, fuck it, if they paint me out to be a dickhead, they paint me out to be a dickhead,’” says Healy, adding that growing up as the son of celebrity parents Tim Healy and Denise Welch meant that he was already tired of showbiz before he got involved himself.

“I would say something in a conversation [like this one] with you and then the headline becomes, ‘Matty Healy says this,’” he continues. “It’s like I’ve fucking stood up in a bar and been like, ‘Everyone…’ I don’t think that my opinions on stuff matter, leave it to the fucking professionals.”

One such incident came after the singer pledged to only perform on gender-balanced festival bills on Twitter in February 2020. But while anyone familiar with Healy’s politics knows he supports equality – and the bill for The 1975’s Finsbury Park one-dayer (cancelled due to Covid) featured seven supports acts, six being female – he says he wasn’t quite aware of the implications of his social media post.

“I was basically saying I’m up for pushing for [equal festival bills],” he says. “I didn’t realise [what] I’d agreed to. I’m not making some claim, I’m not dying on that fucking hill. I could have been on Xanax on Twitter, who knows? But I’m definitely a progressive.”

Now, he prefers to stay on safer ground with his public utterances.

“I make music, that’s what I’m really, really good at,” he reasons. “I’ll make jokes, I’m good at that, it can be argued. I want to make jokes, that’s what I do, really. I know they’re long-form and they’re in music, but there isn’t a good line of mine that isn’t a joke. I don’t want to pretend to be some mouthpiece for anybody apart from me. I don’t fucking know what I’m talking about.”

Such self-deprecation is common for Healy – who calls himself a “man-child” and has his passport number tattooed on his wrist so he “never has to get it out of my bag” – but there are some subjects about which he can claim to be an expert. Chief among these is The 1975, the band he formed almost 20 years ago at school in Cheshire. Healy could talk about The 1975 all day, and you feel he might, if it weren’t for a busy schedule ahead of a flight to Japan to headline Summer Sonic, the band’s first gig since February 2020.

For that reason, and the now customary protect-pop-star-from-Covid-before-a-flight protocol, we talk via Zoom. Healy is in his living room, his phone propped up on the table in front of his sofa, which is strewn with pale cushions. Wearing a Rage Against The Machine T-shirt (coincidentally, the band The 1975 will replace as headliners at this year’s Reading & Leeds), he’s drinking a can of Coca-Cola and finishing a spliff before switching to cigarettes. At one point, his phone topples and his bare knees loom into view.

“Ha, ha! Boxers!” he yelps, admonishing his phone to “fucking stay on there”.

And so here we are, talking to the frontman of perhaps the biggest band of a generation while he sits at home in his pants. As ever with The 1975, there’s plenty to get through, but there’s only one place to begin.

Being Funny In A Foreign Language is the fifth 1975 record and, given that it follows a two album campaign and the public revelation of Healy’s battle with addiction that nearly broke the band for good, he is especially proud of it.

“There were lots of ideas and I didn’t know where else to go, because I’d kind of been everywhere,” he says. “So I was trying to think of something new and then I just thought, ‘Well, what is a 1975 record?’ Take the frills away, what is the thing that connects? And it’s good lyrics and good songs, which are normally quite catchy.”

To arrive at the 11 songs that make up Being Funny In A Foreign Language, the band’s tautest, most immediate record so far, they focused on stripping away the genre-hopping indulgence that made the 22-track Notes… such an expansive listen.

“You can have Logic [software], but you can’t just be in a band for 20 years,” offers Healy. “So we said, ‘Let’s just play.’”

The enforced pause allowed the band to achieve a sense of calm and they returned ready to rediscover their identity. And while sessions at Real World in Bath and Electric Lady in New York were daily rather than the live-in set-ups of old, they were able to recapture something of what first germinated in Healy’s parents’ garage after school. The chameleon-like aesthetic of The 1975’s recent past is gone too, in favour of black and white imagery and smart tailoring. On the record’s cover, Healy stands on a burnt out car, signalling that the band’s previous chapter, the so-called Music For Cars era, is over (“It’s not a time that I envy or want to do again, I didn’t enjoy A Brief Inquiry... because of Notes... and I didn’t enjoy Notes... because of Covid,” he muses).

“When I talk about the marketing or aesthetic of the new record, one of the main things I’ve been saying is that we’re doing an impression of The 1975,” says Healy. “So, if you were going to rip off The 1975, what would you do? Your outdoor advertising would be bold lettering that subverts the traditional… OK, what would it sound like? It was asking, ‘What are the benchmarks that make our identity?’ And then saying, ‘Let’s rip ’em off better than everyone else does.’”

This approach has led to an album that doesn’t concern itself with flitting through genres, rather, it is guitars, bass, drums, strings, brass, piano and vocals, recorded in analogue and exposed in their purest form.

Healy rubbishes the idea that their decision to record live could be read as a transparent bid for authenticity.

“Cliché is only ever trumped by quality,” he says. “We’re so post-everything I don’t think cliché is anything we need to worry about.”

The record deals with pop-rock, country and ballads, and its love songs (All I Need To Hear, When We Are Together) are intensely intimate. In Happiness, Looking For Somebody (To Love), Oh Caroline and I’m In Love With You, meanwhile, The 1975 have hit upon some of their poppiest music yet. Wintering, too, is a Healy masterclass. These are songs that will stick. Indeed, second single Happiness became their 24th Top 75 UK hit just after the band left for Japan. It has some way to go to match their biggest, Chocolate (1,474,129 sales) and The Sound (1,063,155), but it does boast over nine million Spotify streams across the original and a Dance Floor edit. The 1975’s 11.5m monthly listeners are primed for their return and Dirty Hit’s physical offering around the album (there are bespoke zines as well as vinyl, CD, cassette and merch bundles) means there’s a lot to collect. Their self-titled debut has 732,782 sales to date and follow-up I Like It When You Sleep, For You Are So Beautiful Yet So Unaware Of It has 450,146. Those numbers will be hard to beat, but there are enough big choruses on Being Funny… to suggest it may yet match up.

A casual look at the credits could prompt an easy conclusion about its poppier tendencies. Alongside Healy and Daniel as co-producer is Jack Antonoff, who has made hits for Taylor Swift, Lana Del Rey and Lorde, among others. Antonoff is not among the co-writers, but the record does boast the most external input of any 1975 album yet, with Ilsey Juber (Miley Cyrus, Harry Styles, Kacey Musgraves) and Jimmy Hogarth (Amy Winehouse, Sia, Dermot Kennedy) among the writers.

But even though Healy and Daniel did visit the city for a writing trip, The 1975 have by no means gone head first into the LA hit factory. Healy paints a picture of friends and friends of friends dropping by the studio. Dirty Hit alumni Benjamin Francis Leftwich and Beabadoobee collaborator Jacob Bugden are also involved, while guitarist Hann’s wife Carly Holt and Michelle Zauner (aka Japanese Breakfast) contribute vocals. Also present is producer BJ Burton, who they had initial sessions with before deciding to go with Antonoff.

The question is why, after four albums working largely on their own, did The 1975 change tack? They had worked with Arctic Monkeys producer Mike Crossey on their first two, but from then on, Healy and Daniel took charge.

“The reason bands split up, unless there are sexual relationships, is normally ego, money or a combination of both,” Healy says. “Now, because we’ve been a band longer than we’ve been adults, we don’t have that hierarchy. There’s no, ‘Oooh Matty’s getting a bit big for his boots...’ You make a decision and it’s like, ‘Well, why wouldn’t we do that?’”

Aware of the attention around Antonoff’s presence, Healy stresses the importance of Daniel’s role, cementing the idea that it was very much a case of the two of them letting the star hitmaker into their world. Daniel, Healy says, was excited to watch his bandmate “riff with” Antonoff.

“It was like, ‘Well, what are we worried about?’” says Healy. “That people think we might be trying to be bigger? It’s like, ‘Listen to the album’. We’re not trying to do anything. I wanted to make something really live, catchy and now, and Jack does that in his fucking sleep. We were talking all the time anyway, so it just made sense.”

Pressed on the subject of whether he wants a hit single, Healy says he genuinely isn’t fussed.

“If I started caring about that now it would fucking stink,” he says. “I said this ages ago, everyone wants us to become a huge rock band and we want to become a small emo band. If we become Burial, I’m way happier with that than fucking Foo Fighters, do you know what I mean? I love the Foo Fighters, but I couldn’t do that. I couldn’t do that. I’ve never thought about that. It’s funny, there’s something about me that is very poppy and the stuff that comes out is poppy, but the references never are.”

One thing he will admit is that his songwriting has shifted. The borderline cheesy wryness is still there (‘Am I just some post-coke, average, skinny bloke calling his ego imagination?’ goes Part Of The Band), but Healy says “mindful” thinking resulted in more truthful, “episodic” songs, “like polaroids rather than a magnum opus”.

He points to the idea of The 1975 being at ease in their own skin, and that feeling pervades the record. But while the singer posits that he’s got “nothing to prove” on this album, it could be argued that he has. After A Brief Inquiry… came out, The 1975 won two BRITs and two Ivor Novello Awards and headlined Reading & Leeds, as well as a sold-out arena tour. Yet instead of chasing even greater success, Healy recoiled, burying himself in making Notes…, which would surface at the height of a pandemic that prompted the cancellation of The 1975’s entire touring itinerary.

“If I won a fucking BRIT now I’d be like, ‘Oi, oi!! You fucking [what]!’” Healy says. “But I was this fever dreamy, suspicious… I couldn’t really grasp it. We became this new thing and people started using crazy words like ‘Radiohead’ and that’s where Notes… came from. I was like, ‘Fuuuck this, I don’t know how to react, I don’t know what to do.’ I did feel very much on Notes… that our mainstream audience was being tested by my interests.”

Added to that was a backlash following a tweet relating to the death of George Floyd in May 2020. “If you truly believe that ‘ALL LIVES MATTER’ you need to stop facilitating the end of black ones,” Healy tweeted while including a link to Love It If We Made It – a song which features lyrics about racism and police brutality, among other subjects. It was met with accusations that the star was using a tragedy to market his music. Healy promptly exited from social media soon after. Altogether, it felt a little like The 1975 had disappeared just when they should have been about to scale a new peak.

Jamie Oborne remembers the start of the pandemic like it was yesterday. When the world first stopped in March 2020, before the true trauma of Covid would put bands and pop music into perspective, the pause offered respite.

“I was really pleased to get the band off the road, honestly,” he says, sitting in baggy linen trousers opposite Music Week in Dirty Hit’s West London office as the occasional tube rumbles by overhead. “Matthew and I were playing this game of egging each other on to do the impossible. We were all a bit fried. I don’t think we would have stopped otherwise, we would have kept carrying on until… someone would have been ill. It wasn’t particularly healthy, the octane we were working at.”

Oborne can now reflect on the decision to release two albums back to back with the benefit of hindsight.

“I wouldn’t fucking recommend it in a million years if anyone’s got any sense!” he says, collapsing into laughter. “I don’t know what we were thinking. We were just trying to push it forward. It felt very modern and of the time, didn’t it? It felt very urgent and powerful.”

Nevertheless, Oborne says he wouldn’t change the decision and points out that Notes… is the 1975 album that people tell him they love most. He and Healy say there’s something special about the way it stands as a document of the pandemic. What’s more, Oborne isn’t concerned about its relatively modest sales figure.

“I wonder how much of that was the impact of the pandemic,” he says. “No one was really focused, news was elsewhere. I’m more interested in an ever-growing career or catalogue of incredible music as opposed to a track that has a moment in time. Don’t get me wrong, we’ll take an accidental hit along with every other record company, but I’m not kept up at night thinking that I need to have a viral hit.”

Oborne wants to work with artists that define music and culture, and his belief that The 1975 do both has been unshakeable since he first went to the North West to watch them after a tip-off via MySpace.

“I really feel like we have pushed things as far as possible while being a band,” he says. “Whether it’s commercially, creatively, critically, in the live arena, in the studio… Whatever part of the discipline of being an artist is, the boys have pushed it as far as they possibly could.”

The task for Dirty Hit, which is now releasing and distributing The 1975 independently after Oborne chose not to renew its JV with Polydor/Interscope, is to figure out how to push it further still. How can they step up to being the Glastonbury-headlining, stadium-filling band he still believes they can be?

“You make a record with more humanity, which is what we’ve done, its sonic identity and the life in it make it feel really fresh,” says the manager. “Then you make shows that have the same in them. I think it’s a success that we can sell 140,000 tickets in the UK while putting out really uncompromising music. They’ve had four UK No.1 albums back to back, it’s a pretty small fucking list of [bands who have done that]. I think there’s a lot [still] to offer.”

Agent Matt Bates of ICM Partners says there’s no limit to what they can do, despite the cancellation of a host of global dates in 2020.

“They have returned bigger than ever,” he says. “It would have been great to have had all the shows we planned in 2020 play out, but you try and find the positives from a difficult situation and having the extra time away has made the return even more special. Not many artists’ first shows back are headlining Summer Sonic and Reading & Leeds.”

The 1975’s Finsbury Park takeover was set to be the most sustainably responsible show ever held there and while there are currently no plans to reschedule it, Bates suggests “a big summer” awaits in 2023.

“They’re one of the biggest, most important live bands in the world,” he says. “Having them back is good for the fans, industry and beyond.”

Oborne adds that Healy and the band are eager to get back on the road, with US shows coming later this year and a UK arena tour to follow in 2023 (he drops a cryptic hint about “working with a really cool partner” for one show in particular). And while he admits that life in The 1975 is rarely straightforward, he suggests that things promise to be simpler this time.

“I look at the impact and [think], ‘Christ, we’ve built an entire other business around The 1975 in Dirty Hit,’” he says. “The beauty of having managed a group for 15 years and of them having been in a band for 20, is that there’s a freedom there. We can be honest with each other, challenge each other, deal with difficult subjects and have arguments.”

For Oborne, it’s a special bond.

“It feels like a permanent relationship, and you have to work towards that, it takes time, effort and nurturing,” he says. “Luckily, we’re still doing that with each other, which is unusual in this business.”

He won’t say it directly, but Oborne has hit upon the uniqueness of The 1975 in the music industry – the bond between artist and manager/label boss drives not only the growth of the band itself, but of the record label that was built to release their music.

Healy, who says he couldn’t be more excited about the future of Dirty Hit (“We break up-and-coming artists and that’s what excites me”), points out that he’s grateful to be able to say that the relationship with Oborne is more equal these days.

“Jamie’s essentially always been a bit like my dad, or my older brother that I listen to,” he says. “But like my relationship with everybody in my life, there’s been a tinge of woe about my drug addiction. I was a very difficult person to manage, not just from a creative perspective. Actions not only speak louder than words, they’re the only thing that actually make any change, and we’ve now entered a period where my actions have allowed people to be a lot calmer around me. People aren’t worried about me that much anymore and when you take that out of the equation, it’s meant that me and Jamie have been able to come onto more of a similar level. I’m just a bit more professional now, and that makes our relationship easier and better.”

In the music industry, Matthew Healy says he’s been offered “all the wrong things for the right money”. This spindly songwriter in boxers, it turns out, could have sold out big time.

“I’ve never taken [those offers], and it’s not that I’m proud of myself for that, but that part of me has been tested,” he says.

And there’s no chance of him going solo, either.

“We’re a band, we’ve survived because there are four of us, I wouldn’t have survived out here without my boys,” he says, emotion pricking his words. “The idea of the band is what I grew up with, four individuals that create something bigger than themselves that then becomes impenetrable. The band is the cool thing.”

For Healy, this is what sets The 1975 apart, that in an era bereft of mainstream bands, his is a global phenomenon.

“Letting me decide what’s good is like the Wild West,” he says. “I don’t think about setting precedents, but we’ve never really been in anyone’s lane. I’m not saying we’re the fucking Premier League and everyone’s below us, but we’ve never been in anyone’s way and no one’s ever been in ours. The big, credible, new modern band is a very, very tiny genre. I mean traditional, big bands that are still exciting that aren’t legacy acts… Yeah, I can’t name many of them.”

For that reason, he doesn’t see the need to conform to pop tropes.

“I’m not particularly concerned about growing old as a band and continuing to put out records, because we’re not remotely commercially minded,” he says. “Which inherently keeps us, I don’t want to say credible… We’re just four nerds who are obsessed with alternative music and pop culture, it’s no deeper than that. I’m not worried about us being like, ‘Oh shit, we need do a fucking remix with Marshmello.’ I’m very comfortable with where we are.”

Healy’s clear-headedness stems from an effort to “condense” his life. He’s hitting the gym, practising Jiu Jitsu and eating healthily (“chicken breast and rice and shit”). Spending time mostly at home or with his bandmates, he avoids the radio (“except LBC”) and has time to think about the music industry and The 1975’s return to it.

“Mainstream pop music doesn’t really tickle my fancy,” Healy says. “I understand the tropes and the apparatus and it just feels like somebody’s built a machine. I’ve never been on a major label, so I haven’t learned that world.”

He’s not likely to end up on a major any time soon either, but Healy’s indieness doesn’t prevent him from taking a keen interest in streaming (lest we forget, Notes… did feature a song with that very title). Catalogue is his latest rabbit hole.

“The consumption of the catalogue of a band can happen over a very long period of time, which is a good thing,” he says. “But what we now have are these nights of falling in love with your new favourite band and knowing it’s for real. It works so well for The 1975, because what that gives is context. You can look at videos or reviews, but if you go on Spotify, the full context is there, ranked by what people like. The discovery of catalogue has made me think differently.”

Specifically, he’s thinking about reviving older songs.

“You can’t know what a fan favourite is going to be,” he continues. “Say you make an album and you make four music videos, because they’re the four singles. Then the album comes out and there’s a fan favourite, because there always is, that isn’t any of the singles. That song doesn’t have a video, so why can’t you make one for it when it materialises as a fan favourite? Not to be commercially minded, to be in service of fandom. Not to look at it as a way to exploit and get more views, but if everyone’s favourite song is [2013 1975 track] Fallingforyou, why isn’t there a video for it? We’ve bent time so much, it doesn’t matter.”

Healy exhales with the manner of someone who’s just about done putting the world to rights, for today at least. Before we leave him, there’s one last thing to clear up about interviews with Matthew Healy.

“Don’t mistake my progressivism for being totally woke all the time, because it is a bit self-serving, I’m an artist and I’m interested in art,” he says, tapping the table in front of him. “Of course I want equality of opportunity and all of those things, I’m an old school progressive. But the thing I’m a bit annoyed about is, I don’t want to have to fucking say that. It’s implied, I’m bored of commenting on the morally obvious.”

By now, Healy says, those with any interest in what he says should know what he stands for.

“Yeah, I’m anti-racist, yes I’m anti-fascist, yes I’m pro-women, of course I am,” he concludes. “It’s like, ‘We fucking get it, let’s try and figure it out.’ I’m definitely into the conversation, but I’m not into the performance of it.”