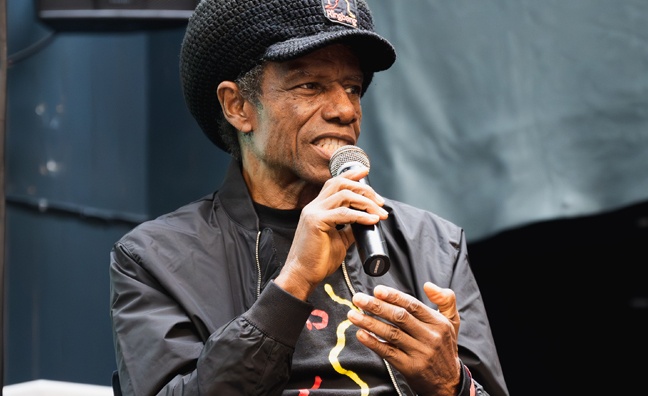

It’s a busy time to be Eddy Grant. This Friday (April 26), he will be speaking at London’s Beyond The Bassline exhibition, which documents 500 years of Black music in Britain. He’s also currently hard at work on his autobiography. And what’s more, the legendary artist has recently released his multi-platinum album Killer On The Rampage – which features the smash hit Electric Avenue – on streaming services for the first time.

Here, he tells Music Week about all of the above, plus gets to grips with the threat of AI, reflects on the ups and downs of life in the business and much more besides…

You’re taking part in the Beyond The Bassline exhibition, which documents 500 years of Black music in Britain. Does it present an opportunity to reflect on your contribution to that story? How are you preparing for it?

“There’s really nothing to prepare. I’ve been prepared over the… centuries (laughs) that I’ve been around. It’s that experience, knowledge and capacity that means I’m able to talk. I’m able to talk about things I’ve seen, I’ve heard, and that I’ve been taught. I’m also writing my autobiography as we speak. But there are many sides to everything. Musically, I came from a number of places, but the one you might know of is The Equals. I give a lot of credence to that time and what we achieved. It’s never really given the credit I think that it should. Maybe we will get a chance to put some of that right.”

And how’s the autobiography coming along?

“Oh, don’t ask! I’ve been doing it for a long time. It’s in its first draft, but maybe there will be 10, I don’t know. As you go along, you realise, ‘Oh Christ, I didn’t think about that’ or, ‘I better leave this out because I will hurt this person.’ You have all these psychological barriers to cross when you’re writing a book that is meant not to be sex, drugs and rock’n’roll.”

The history of dance music will not be the history of dance music without my music – I’ve been sampled like you cannot believe

Eddy Grant

How much of an emotional undertaking is unpacking that journey?

“Very emotional. But by the same token, so is writing a song of any value. You have to put something in to get something out. So, for me, it’s just like writing a long song. Things will come out of that process. You will see a picture emerging. It’s like stripping years and years of wallpaper away. We’re well past the deadline. I was given last June as the date. Now we’re fast approaching the next June and maybe even the next June. As long as it’s good [when it does arrive].”

Do you recognise your influence and legacy when you look at modern music?

“Oh, no doubt about it. I’m amazed – the degree to which it’s obvious – when I read, see and hear it, without blowing one’s horn. But if people don’t know, then you have to tell them. The history of dance music will not be the history of dance music without my music. I’ve been sampled like you cannot believe. History, even in its biasedness, cannot leave me out. I understand what’s going on and what has gone on, relative to myself and to the business, and the degree to which I have contributed. But that’s what I set out to do. So, it fills me with pride. I find today, new kids on the block are using my music as a point of reference, using my life as a point of reference, and that would fill anybody’s heart with joy.”

In recent years the music industry has made concerted efforts to improve representation and diversity across the board. How have you viewed that?

“I know the beast of which you are speaking. I know the way it moves by day and by night. There has been a move towards inclusivity. For a time, there was a mad rush to placate people darker than blue. [But] I think that it was a knee-jerk reaction. As a person consciously looking at the environment, I could see it, I could smell it and… it’s not genuine.”

You’ve started gradually releasing your catalogue onto DSPs for the first time. Why did you resist it for so long?

“When I first consciously decided I wasn’t going to do [put my my music on streaming], I had a plan in mind, like I suppose every other artist like me did. I waited years for the digital dissemination of music to come about. When it did, I recognised, ‘Woah, this is not in artists’ interests.’ Government should have been able to dictate it – just like they have with other things – and say, ‘These are the parameters, guys. Work it out.’”

Do you think a generation of music fans might have already missed out on discovering your music?

“There’s an element of that. That’s really why I decided to come out, so to speak. People don’t give one flying shit about the rights and wrongs of it, they just want choice. And if that choice is £10 a month for thousands of tracks, hey, I’m with them, I understand. I listened to what my fans were saying, and I gave it the go ahead [in the end].”

Does it feel like losing the battle or can something yet be salvaged by joining in?

“Listen, I joined in when it was analogue recording, when it was vinyl and you had to pay 30 per cent… I’ve been there. I understand the process, so it’s no big jerk. It’s just that, I think to myself, ‘Well, no one is really interested in what’s fair anymore.’ Fairness doesn’t come into it. Maybe it’s always been like that. Maybe it’s going to continue being like that. Maybe I just have to join the bandwagon, but hey, that’s how it is. The industry is bifurcated. It’s overtly fair to some and totally unfair to those it doesn’t give a damn about. Which, I suppose, is human nature.”

So what are your personal reflections on dealing with the business side of things?

“Well, since 1969 I’ve had my own label situation. Albeit, you’ve still got to go through somebody else for certain things. You’ve got to love someone! It always has been a question of your ability to compromise or not. I always say, ‘What do you call a bad guy with a gun? You call him sir.’ That analogy is what it’s like being in a massive industry that is now controlled by maybe three or four people. When you think about it, maybe it was always like that, behind closed doors. It’s not an issue that someone necessarily has to complain about. You’ve just got to make hits. I don’t think there was ever any good will towards what it is I was trying to do or what I was trying to say. It is by force of goodness, by force of creativity, that I am here now speaking to you. If I hadn’t had the capacity to write those songs, or to find somebody to record them, I wouldn’t be here.”

What are your thoughts on how technology and the rise of AI might impact the future of the industry?

“I am not scared of it. I welcome it, in a certain capacity. Because it’s a tool. It’s like when drum machines and synthesisers came out people said they would put players out of work. Creative people remain creative and non-creatives will still sound like shit. There’s nothing to be frightened of.”

Finally, is there any new music on the horizon for you?

“I’m always [working] two albums ahead. That’s what I do. I make music. My creative hours are spent creating and I have so many things going on right now. It’s all about time. I’m 76 years old and I’m not going to live forever. Please god no… You’ve got to manage time, in as much as one can. Things happen and you have to deal with them – emotive things, business things – but be assured, I’m always two albums ahead.”

Eddy Grant will appear at the British Library to launch the Beyond The Bassline season. The evening will be a retrospective conversation with Colleen “Cosmo” Murphy about his career. The event takes place Friday, April 26 at 7pm: https://beyondthebasslineevents.seetickets.com

Interview: David McLaughlin

Photo: Gavin Mills