Today marks the 40th anniversary of Blue Monday, a landmark release by New Order that’s widely acknowledged as the biggest-selling 12-inch single of all time.

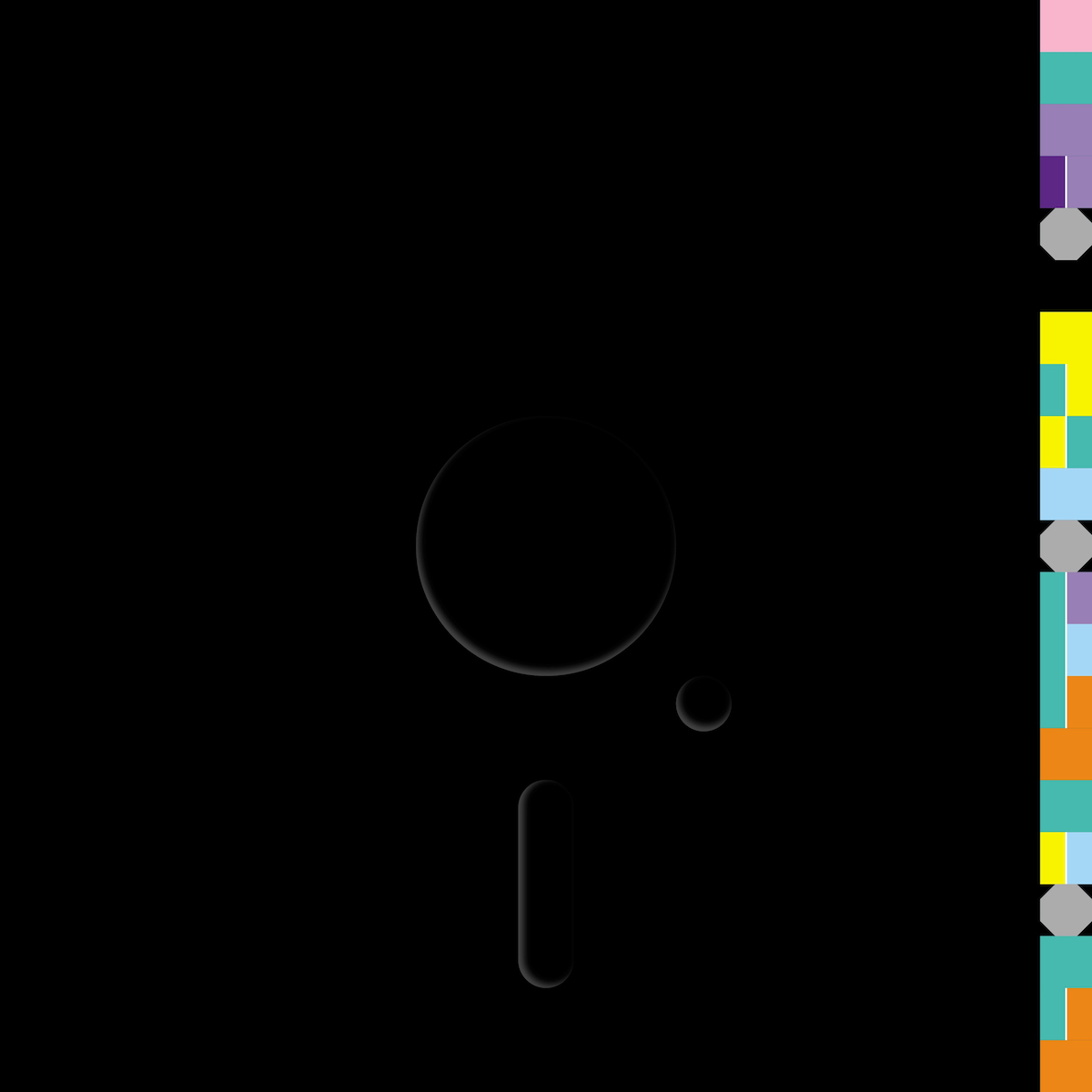

New Order - and this particular song - do attract certain myths. For instance, in his memoir drummer Stephen Morris has dismissed the claim that Factory Records lost 5p on every copy of Blue Monday sold because of the expense of producing the die-cut sleeve based on Peter Saville’s design, inspired by a 5 1⁄4-inch floppy disc.

So is the sales record another part of the Factory Records mythology that doesn’t stand up to scrutiny? Actually, Music Week can confirm that New Order’s claim to the biggest 12-inch single of all time still looks pretty solid four decades on from its release.

Running to seven minutes and 29 seconds, Blue Monday had a 38-week run in the Top 75 in 1983, peaking at No.9 in October. The sales performance of the 12-inch single was helped by the fact that the track was not included on that year’s New Order album release, Power, Corruption & Lies, and it was not then sold in a seven-inch single edit. The 12-inch effectively had a captive audience until the band’s Substance song collection in 1987 and a seven-inch version the following year.

With the Official Charts Company only tracking sales consumption after 1994, it’s not possible to fully verify the claim for Blue Monday. But its status as the biggest-selling 12-inch was strengthened by the OCC including it at No.69 in a list of the UK’s million-selling singles in 2012. While downloads would have contributed to its then total of 1.16 million, the bulk of that sale was on 12-inch vinyl. The vinyl revival of the last decade or so has been focused on LP, so no 12-inch single release has amassed significant sales in that period to rival Blue Monday.

Although there’s no BPI certification to confirm the claim, that’s likely explained by the fact that Blue Monday was independently released by a label and distributor who were not members of the trade body at that time.

Music Week charts analyst Alan Jones wrote about the Blue Monday sales phenomenon in the May 1988 edition of Record Mirror. At that point, its UK sales were reported at 800,000 and two million worldwide. According to a statement for the 40th anniversary, it now has three million sales worldwide across physical and digital formats.

Blue Monday sleeve designed by Peter Saville

Blue Monday sleeve designed by Peter Saville

Following the band’s US deal with Quincy Jones’ Qwest label, the legendary producer supervised a new mix of the single. It was released on seven-inch for the first time and, as Blue Monday 1988, peaked at No.3 in the UK. A later release, Blue Monday 95, peaked at No.17.

New Order signed to London Records following the demise of Factory in 1992. The band’s catalogue, which was under their control, later moved to Warner Music in the mid-noughties. Rhino recently released the definitive edition of Low Life.

Post-1994, Blue Monday is by far the biggest New Order track with chart sales of 1,202,345 (Blue Monday 1988 is on 42,262). The original version is now established in the streaming era, with 95,910,661 streams (audio and video) logged by the Official Charts Company (which equates to 901,078 ‘sales’), as well as 286,712 downloads and 14,588 physical copies.

It means that New Order’s UK chart sales for Blue Monday since 1983 are in excess of two million across all formats.

Globally on Spotify, Blue Monday has almost 318 million streams, with a further 110m for the 1988 mix.

Blue Monday has soundtracked film releases, video games and advertising campaigns in recent years, including House Of Gucci, Ready Player One, Atomic Blonde, Wonder Woman 1984, the Call of Duty game series and Yves Saint Laurent. New Order and Joy Division music is currently prominently featured on BBC crime drama Gold.

To mark the 40th anniversary of Blue Monday, Music Week spoke to engineer/producer Michael Johnson, who worked on the track and went on to record three albums with New Order. He had previously worked on Joy Division’s final album Closer as assistant engineer.

Here, he recalls his time in Britannia Row Studios in Islington helping to create the classic single, which he engineered alongside the band who were self-producing…

What can you remember about the atmosphere and recording process in the studio?

“They had most of Blue Monday programmed beforehand - the drums, the bass, most of the synths were programmed. So we recorded those and then we started doing overdubs later in the session. Hooky would always be in the control room, sitting on my left by the mixer reading a book and telling stories. The others would come and go. Sometimes they'd be working things out in another room, having a cup of tea, playing pingpong or snooker. But Hooky was almost always there the whole time.”

How was the programming on the track because the process sounds fairly tortuous?

“Most of it was done before the studio, they had their own rehearsal room. They added stuff afterwards. Steve [Morris] was working on a speech synthesiser on an Apple II computer to try and get it to stutter, ‘How does it f-f-f-feel?’ We didn't have MIDI Timecode in those days, so we only had 22 tracks to work with - two of the tracks were being used for sync pulses. So we had to put lots of different things on the same track. I inadvertently wiped the speech synthesiser while we were recording something else. He wasn't very happy about it but couldn’t be arsed to start again. I don’t know if he’s ever forgiven me.”

What do you think you brought to Blue Monday?

“Hooky’s book credits me - I don't remember this - with suggesting that he play bass on it. Originally, they weren’t meant to be playing on it themselves. It was an idea for a piece to play as an encore at gigs - press a button, the music would start and then they could go to the bar or get in the car and clear off. But when I suggested putting the bass on, that changed it completely. So it became a group song, and then it was probably Rob Gretton, their manager, who suggested that Bernard [Sumner] write some lyrics and sing on it. So then we started adding things to it. We'd already added a few sound effects and samples, like the sound of a thunderstorm that Bernard had recorded himself. Then there was the famous Kraftwerk sample, the choir, which they had sampled from somewhere else. So I was very involved in the sound of it. For the famous bass drum sound, we sent it through a big studio monitor, which they had in the games room and we miked it. So I did have quite a bit of input when it came to the studio.”

Did you get any kind of producer credit?

“No, I did get that on subsequent albums. For the next three albums, I did get royalties on those. They didn't give me any production credit but they obviously thought I was at least a co-producer in that they were paying me a royalty.”

What equipment were they using for Blue Monday?

“The Oberhein DMX drum machine, the Prophet, there was a Moog Source bass line, the Quadra was a string machine and synthesiser in one. The Oberheim DMX drum machine was digital but the synths were all analogue.”

And there’s something a little out of time isn’t there?

“Yeah, there's a little synthesiser line that to sequence they had a very primitive sequencer where you had to virtually enter it in as code, it was very difficult to use. Gillian [Gilbert] had to keep a record of what she put in and what she had yet to put in, she wrote out the sequence by hand on A4 paper all sellotaped together into a big long roll. I think when she was inputting it, she added one sixteenth rest too many and that put the sequence slightly out of time. But when we listened to it sounded really good. It just had to get the right volume and it gave it a lift, it really bounced the track along. So it was a happy accident.”

What do you recall of the infamous Top Of The Pops performance, where New Order attempted to play it live rather than mime?

“Well, I was there. I was supposed to be helping out with the mix but, with the BBC being unionised, I wasn't allowed anywhere near the mixing desk. I was stood behind and trying to advise them. As far as we knew, that was just a run-through and there would be another take. But the director said at the end of it, ‘Okay, next set-up’, and they wouldn't let them do it again. So they weren't very happy with it. I don’t think the BBC were particularly happy either, but they weren't prepared to let them have another go. So we had to go with the mix that we had, which wasn't great.”

New Order photographed by Kevin Cummins in New York, 1983

New Order photographed by Kevin Cummins in New York, 1983

Didn’t Kraftwerk end up working with you because of Blue Monday?

“Yeah, they got in touch with the studio. I think they'd heard Blue Monday in a club and were knocked out with the bass drum sound, they wondered how New Order had got it. I think they phoned up Stephen and found out where it had been done. There are various different stories about that. Hooky’s story is that they were disgusted with the studio and didn't believe that it had been done there and stormed off in a huff, which isn't quite true. I was a little bit out of my depth on that, I was a bit overawed by Kraftwerk and expected them to direct the proceedings. But they just sort of sat there and expected me to do a remix of it [Tour De France]. It really wasn't the way I was used to working. I was a new engineer. Power, Corruption & Lies was the first album I’d recorded as an engineer on my own. But I read Karl Bartos’ book [The Sound Of The Machine] that came out last year and he was quite complimentary, he certainly didn’t say they stormed off in a huff.”

How was it working on Power, Corruption & Lies, which is widely seen as the first fully-fledged New Order album?

“Yeah, I think they'd decided to produce themselves. They had done a couple of singles themselves. They were never happy with what Martin [Hannett, producer] did. I think in retrospect, looking back at the Joy Division stuff, they realise that he did a great job. But at the time, the sound that he got was nowhere near what they wanted for themselves. When it came to Power, Corruption & Lies, they had changed their direction completely. They were much more influenced by dance music, by what they had been hearing in clubs. So the shackles were off and they really blossomed.”

Finally, how does it feel (to quote the lyric)... to have been involved in such a classic?

“It's bizarre that it's almost the first first thing I did really and it did so well. My first week in the studio was doing sound effects for Pink Floyd’s The Wall, and we recorded the children for Another Brick In The Wall [Part 2]. So the first thing I ever actually recorded that was released was a Christmas No.1. And then Blue Monday, recorded a few years later, is the biggest-selling 12-inch ever. I’ve worked my way down steadily since then!”