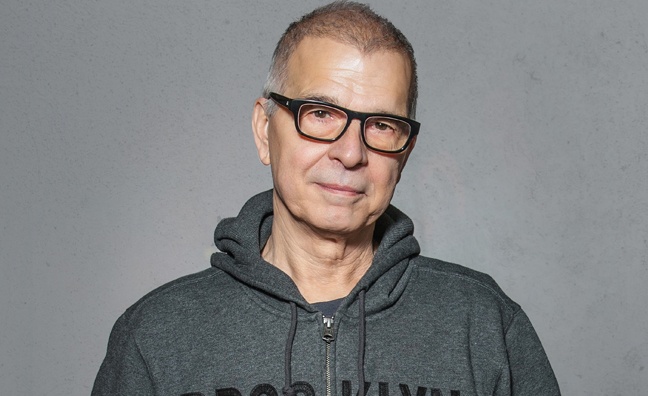

Super-producer Tony Visconti has shared stories from his fabled near 50-year partnership with David Bowie in an interview with Music Week.

The pair, who first collaborated on 1969's Space Oddity, formed one of the all-time great artist-producer partnerships, working together on and off until Bowie's final album Blackstar, released two days before the icon's death in January 2016.

Bowie rarities set The Width Of A Circle is released via Parlophone today (May 28) as a companion piece to the 2020 50th anniversary re-release of The Man Who Sold The World, which restored the album's intended title Metrobolist and included a new mix by Visconti.

Here, in a special Q&A, the 77-year-old American tackles a host of Bowie-related subjects, from their first meeting in London to the Thin White Duke's BRIT Award-winning swansong Blackstar...

What David always needed from me was validation

Tony Visconti

What were your first impressions of David Bowie?

"I met David in my publisher’s office. My publisher had played me the first Deram album, where David was doing Please Mr Gravedigger and all those original, very interesting songs. They had more of a root in British musical theatre and I really liked them. The first thing I thought was that he had a great voice. If an artist doesn’t have one, it’s extremely hard to make a great record. I met David within 15 minutes – we were left alone together and got on immediately. We realised we loved the same things, so we spent the day together and talked and talked. We loved the same things like Frank Zappa, Mothers Of Invention and an early protest group in America called The Fugs, who actually used profanity in their records and that was pretty radical in those days. And we both liked foreign movies. We took a walk down King’s Road and ended up seeing [Roman Polanski's] Knife In The Water. We got on like a house on fire that first day.”

How did your relationship develop from there?

"By The Man Who Sold The World [1970], we were really tight. We were living together with our girlfriends and half the band at Haddon Hall in Beckenham. We spent at least a year under the same roof with seven people and one tiny kitchen. We rehearsed The Man Who Sold The World in the wine cellar of the house. But we fell out [over Bowie's choice of manager] Tony Defries. We parted company and didn't even speak for two and a half years. But after that we got together on a project – it might have been Diamond Dogs [1974] – and by then David was a more confident person. He could call the shots with his managers. He was in a good headspace and I was in a good headspace. So I would say from Diamond Dogs onwards, we were a team, but we gave each other permission to work with other people and he went off with other producers like Nile Rodgers and made some great records. I didn’t need David Bowie to make a living, but of course he was my favourite artist to work with.”

How did David take to direction in the studio?

“What David always needed from me was validation – that’s it. But I get the feeling he always liked to sing to me. He’d look at me and if I would give a thumbs up, that gave him confidence – right to the very end. I even asked him, ‘Why are you still working with me?’ And he answered that with just a very big grin. I really can’t put it into words how he took direction because we worked more as collaborators than me being the boss of him. I mean, we kept reversing those roles – he would be the boss of me, I would be the boss of him – depending on what activity we were doing like playing, singing or even writing backing vocals."

What sort of interaction did you have with John Lennon during the making of Young Americans?

“None whatsoever. Young Americans [1975] was finished and I took the masters back to London, where I had my own studio. Just before I left for London, I’d spent all night with John, David Bowie, Ava Cherry and May Pang. We all left the party at 10am, so I had a great chat with John Lennon and asked him all the Beatles questions I could think of. He was affable and kind, a very nice guy. But then after I’d mixed the album, David said to me, ‘John and I decided to write a song together. We went into the studio last night’, so it was a fait accompli. I couldn’t fly over just for one song and it hurt my feelings, quite honestly. But Fame turned out to be absolutely great and was the single David needed. I don’t think much of Across The Universe, but Fame is just fantastic.”

Lodger is arguably the least heralded album of the Berlin Trilogy, do you feel it is underrated?

"We always thought it was great. I put my finger on it during the making of Blackstar; we had a lot of time on our hands – David would take two weeks off a month for his own reasons – and during that period I pulled up Lodger and started remixing it, because it just didn’t sound as good as “Heroes”. We mixed it when he was playing The Elephant Man on Broadway in a terrible recording studio in New York City and it was a disaster, but he was on a schedule and we had to release it. We regretted that mix all these years, so I mixed five songs behind his back – he was flabbergasted when I played it to him. I finished the album and Lodger was re-released [in 2017] in the new form. Some people say, ‘Oh, I like the original’ but most people like the remix because it sounds more like Scary Monsters. All of the flash and technical fairy-dust that Scary Monsters has, I used for Lodger. David said to just go ahead and do it. In his later life he didn’t want to attend mixes any more, he wasn’t interested. He trusted everyone who did his mixing for him.”

Why did David never tour again after 2004? Did he ever come close?

“No. If it ever did come up, he said he was finished with it. He didn’t enjoy it and it wasn’t important to him. And for a person who did probably 1,000 shows, I would take that as a definite ‘yes’ that he was fed up and had had enough.”

Lastly, what does Blackstar mean to you personally?

“Well, everyone involved [in the recording sessions] knew that David was ill, so it was no secret and it was hard to take. He told me he’d been having chemotherapy and the next day he told the band and said, ‘We’ll just get this out in the open so we don’t have to talk about it again’. Apart from the shock of those first 10 minutes, the album went on without discussing it again and he was in great form. He said, ‘I always wanted to make a jazz album and this is the closest I’m going to come to it’. If that’s the last thing he left, we’re blessed because it is an excellent album. But according to him, he’d already started writing for the next album. I’ve never heard the music, it’s probably buried somewhere in his archives. But I don’t think any of it will see the light of the day because what he meant by ‘writing’ is that he maybe just wrote instrumental backings. He would always leave the melody and lyrics until he got to the studio.”

By James Hanley